ESSAY, DE GROENE AMSTERDAMMER, 2024

How to Talk About Peace in Times of War

The Palestinian professor Rula Hardal and the Jewish lawyer May Pundak, through their peace organization ‘A Land for All’, aim to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by developing a framework for peace. In doing so, the national aspirations of both Jews and Palestinians must be respected.

Published also in Dutch on De Groene Amsterdammer

Rula Hardel sits on the stairs outside the Cinematheque in the heart of Tel Aviv. A petite figure, dressed in a modern jacket, wearing high heels and a silk blouse. She just drove in from her home in Ramallah on the West Bank. At a distance from the crowd of this anti-war protest, she sways gently as she practices the words of her speech — her unassuming earnestness giving no evidence of her being the new co-CEO of “A Land for All,” an Israeli-Palestinian peace organization.

As Rula takes the stage for one of the final speeches of the event, she begins with a bold statement: “I’m scared. I’ve been scared for a long time, even long before October 7.” This declaration sparks a dramatic outburst from a woman standing behind me in the crowd, accusing Rula of dishonesty. She shouts out that she is a survivor of the October 7 attack. Despite this interruption, and though visibly distracted, Rula continues her speech.

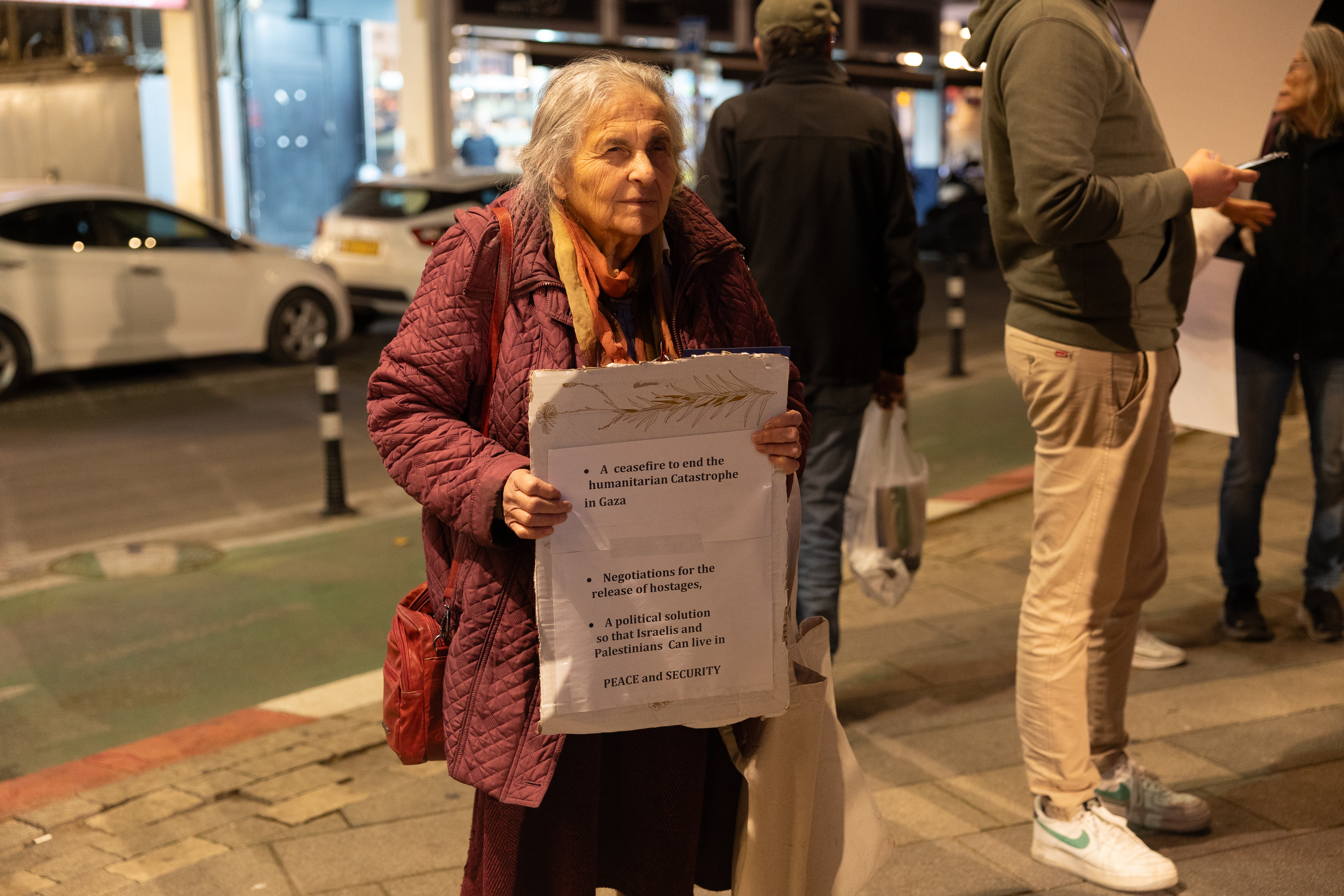

The protest holds just 200 people. It is a rare gathering of Israelis and Palestinians protesting shoulder to shoulder, chanting in Hebrew and Arabic both. We are holding signs advocating for ceasefire, co-existence, peace, the end of Occupation and the liberation of Gaza. These are matters I thought were not being spoken out loud anymore in Israel. Many signs call for a deal to secure the release of the Israeli hostages still being held in Gaza.

Here, I feel the burden of our collective memory of October 7. And in the middle of all this stands Rula, a beacon of resilience. She is simultaneously calling for a brighter future and expressing her rage. With every word, she condemns the harsh reality that has been endured by the Palestinians for many decades. As Rula leaves the stage, she finds herself enveloped by mostly Israeli comrades from her organization. In their midst, her composure cracks, revealing glimpses of vulnerability beneath the facade of her stoicism. When the protest comes to an end, Rula slips away without saying goodbye.

The first time I hear about “A Land for All” is in 2016, another year marked by a wave of violence in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, by Israelis referred to as “the Intifada of the Individuals.” I recall reading Thomas Friedman in The New York Times proclaiming that “the two-states solution is dead.” Over the years, the Netanyahu governments have done everything they could to avoid suggesting or even allowing for any political solution to the conflict. This vacuum has quickly been filled with radical fundamentalist agendas. Thus, for years, both Jewish supremacists and Islamic fundamentalists have been able to build and spread their ideas.

On their website, “A Land for All” advocates for the establishment of two separate states, a Palestinian state and Israeli state, within a confederal system, ensuring unrestricted freedom of movement for all citizens of both states. This contemporary paradigm of confederation models itself on the European Union, where citizens of member states can freely reside anywhere within confederation borders. Such a setup would enable Palestinian refugees to return to the region, albeit not necessarily to their original lands, while Jewish settlers could continue to live in the West Bank, albeit under Palestinian jurisdiction. The blueprint designates Jerusalem as a capital district for both states, with confederally shared institutions tasked with addressing common concerns such as security, climate, water rights and macroeconomic policies. In addition, there would be just reparations for those Palestinians who cannot realistically reclaim their ancestral homes and for those Jews who were expelled from Muslim countries and forced to leave their property behind. Finally, each state would be democratic and committed to principles of equality in accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Reading this outline for the first-time sparked questions, and also suspicion, in me. Saying that both sides have historical claims and are equally right ignores the harsh current reality. But I quickly learn that at the heart of it all, there’s a bold push for living together peacefully, that this is a movement seeking a solution that honors the national aspirations and age-old land-connections of both Jews and Palestinians, without forcing false symmetry. Despite each community representing conflicting ideologies, the members of the movement have been coming together for many years now for what seems like an impossible conversation.

Fast forward to October 7, a pivotal moment for the entire region and for me too. During the bloodiest war in the region since 1948, I travel home, from Amsterdam to Tel Aviv, to grieve and to help friends and family. In January I encounter the organization again, this time with two young women at the helm, sharing the CEO position: May Pundak, a Jewish lawyer from Jerusalem, and Rula Hardal, a Palestinian professor in political science with Israeli citizenship, living in Ramallah. Under their leadership, the organization is being reformed into a solid joint effort between Palestinians and Israelis, boasting a new board composed of seven members from each side.

On October 10, a date that had been set months before, they hold their first board meeting. Those involved in that meeting, and in the activities of the organization since that date, describe the gatherings as particularly touching whenever members meet around its round table. “Think about it,” May recounts, “it was October 10, we were just starting to grasp the aftermath of October 7. I took shelter with my children at my mother’s house, because there were constant sirens, and we don’t have a safe-room in our house. Also, I didn’t want to leave my mother alone. We were all in shock. The Palestinians couldn’t yet imagine what was to come. The air bombings of Gaza had begun, we had experienced many cycles of this in recent years, but it became clear that this cycle was going to be different.”

The board meeting took place over Zoom, with participants scattered around the globe, in Bethlehem, Beit Jalla, Ramallah, Tel Aviv, Akko, London and the USA. The reality of the Israeli checkpoints in the West Bank had made movement impossible — people were literally trapped in their villages. May describes how as she was working on the logistics of setting up the meeting, she was running scenarios in her head: “What if things explode during the meeting? What if they explode from the Israeli side, or the Palestinian side, or maybe people won’t show up at all. I was alone then, I had no Rula yet.”

Around Hanukkah, one of the board members from Gaza lost his wife’s entire extended family in a single air strike of the Israeli army: 23 people, described by May as intellectuals, artists, poets, and peace activists. “Some of our members had sons serving in Gaza right then. Everyone offered their condolences, and his response was ‘We need to triple our efforts.’”

After this meeting, the board asked Rula to take on the co-CEO position. She decided to leave her academic job at Al-Quds University, a decision she hadn’t considered before, as she recognized the urgency of the moment, and she stepped up to the challenge.

In my first talk with Rula — she’s in Ramallah, we talk on the phone — I ask her about the practicality of conducting such conversations during the ongoing Gaza war. With the noise of a hair salon in the background, she passionately explains, in Hebrew, the urgent necessity of introducing a political horizon. Her voice is loud as it competes with an Al Jazeera news broadcast. “Wait a minute,” she says and addresses the hairdresser: “Can you please turn down the TV?”

Realizing she is in a public space, I find it hard to picture Rula speaking loudly in Hebrew, while having her hair done in the center of Ramallah. “I can challenge many stereotypes you have about Palestinians,” she confidently states. “Come with me, and I’ll show you my life in Ramallah. We’re ready for peace, the problem lies with your people.” Rula is aware of the public opinion polls showing that over 70% of Palestinians support for Hamas after October 7. Polls also show only 32% of Israeli Jews support a peace agreement with Palestinians. Still, she insists that a change of mind is more likely on the Palestinian side.

“October 7 was very scary,” Rula says. “It was hard for me when stories of the killings and kidnapping and all the visuals of horrors started coming out. It was hard morally and ethically — on every human level. It was hard that this was done in some way also in my name. My head was flooded with questions that scared me, what does it say about us? And no, I am not forgiving the past atrocities of the Israeli army, but I don’t want to be in the same place. And I knew then that things will never go back to how they were before October 7. I knew immediately that Gaza will change forever.”

Long silence. “Are you there?” Rula’s still on the other side of the line. “Yes. Saying all this, I know that we need political imagination. And some letting go of rightful claims. People need to know that that’s what it is, that letting go is also an act of liberation. Liberation of ourselves.”

Rula tells me that the Palestinian part of the group is still forming. Since the war, it’s been hard to bring Palestinians to the table. They don’t want to think about solutions, about the day after. “It’s easier to find Palestinian participants from 1948, but not from 1967. And I don’t want us to be only ‘48.” I understand that the ‘48 Palestinians she refers to are Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, and ‘67 are citizens of the Palestinian Authority. “They are just not ready emotionally, nationally. But it is a very dramatic moment for all of us.”

This is understandable considering we are 247 days since the war began, that Gaza is under siege, and the death toll among Palestinians is over 35,000. The humanitarian crisis is growing within its displaced communities, and the settler violence in the West Bank is contributing to the overall severity of their situation. Most of the young generation refuses to have contact with Israelis or to consider coexistence, seeing it as a betrayal of their cause. This position leads to their choice of resistance over reconciliation. “Additionally,” Rula explains, “these are people who have almost never spoken to Israelis. They think all Israelis are monsters. We, the Palestinians of ‘48, have seen both worlds. This gives us another point of view, it always has.”

May is ten years younger than Rula, energetic and eloquent. Living in Jerusalem, a mother, she balances work and family. She is also the daughter of Ron Pundak, one of the architects of the 1993 Oslo Accords. She grew up in a politically engaged environment. Trained as a lawyer, she initially worked for the state but left when she realized she couldn’t affect change from within the system. Her dream was to become a human rights lawyer. She embarked on various ambitious projects, such as founding a dialogue group between Israeli and Palestinian youth.

She recounts what was for her a defining moment. It was 1992 she was standing in a protest in Jerusalem, chanting the common anti-occupation slogan at the time: “Israel, Palestine, two states for two people.” She recounts how she turned at one point to one of the Palestinian girls who was holding up the other side of the anti-occupation banner, and said: “Wouldn’t it be a dream come true if we finally had these two states for two people?” The girl’s response was swift and firm: “No. My dream is for you (Israel) to remove your foot from my throat and get the hell out of my land.” After that moment, May’s paradigm started to shift. She began to understand what was wrong with the Oslo Accords and started working toward change. What was needed was the development of a pragmatic and humanistic ability to hold multiple truths at once and to advocate toward more nuanced positions and understandings of the Israel and Palestine conflict.

“A Land for All” recognizes the Palestinian desire for one homeland on all the territory of Israel and Palestine, and the Palestinian refusal of the borders imposed by the UN partition plan in 1947. At the same time, it also recognizes the Jewish historical claims to the land. It takes into account long-standing traditions, religious beliefs, and the land connections of local communities, all often overlooked in western frameworks like the Oslo Accords, constructed according to paradigms of international law. “Instead of seeing these sentiments as obstacles,” May explains, “embracing them can result in an inclusive approach that represents local diversity.” This approach also entails engaging with orthodox Jewish and other factions of the settler communities, communities that are driven by religious sentiments rather than notions of Jewish supremacy. This seems like a fragile aspect of the vision as it does not realistically address the Jewish and Muslim theological beliefs aspirations, which are mutually exclusive and non-negotiable.

May notes the current tension in Israeli society: “Right now, you can’t ask anyone anything. No opinion polls, no media interviews, everyone is militant.” She is referring to the state of mind post October 7, post the Hamas attack with its death toll of 1400 in one day. Extensively documented and even live streamed on social media, the attack has left a profound impact of trauma on all Israelis, those who experienced it up close and also those who didn’t. The kidnapping of 250 Israelis, with 120 still in captivity, has added to the trauma. With over 350,000 Israelis displaced from their homes in both the south and north of Israel, the Israeli government and media have actively been maintaining this atmosphere of existential crisis, intensified by the ongoing war that daily delivers names, pictures and stories of fallen soldiers. Virtually every family has members in the military. These circumstances only exacerbate the trauma. Adding all of the above to the Palestinian genocidal war experience, the situation is even more dire. Who can they turn to for support?

When I sit with May and Rula, their dynamics are visible: May is talkative, openly acknowledging her privilege as a white Israeli while also careful about ensuring space for Rula’s voice. In contrast, Rula seems less concerned with political correctness. Curiously I inquire: “Aren’t you afraid?” She responds calmly, “No.” I press further: “Don’t you receive violent reactions?” She shakes her head: “No, I’m not on social media.”

May and Rula’s schedules cannot accommodate all the invitations they have been receiving to participate in international conferences and meet activists from around the world. Nonetheless, while they feel they must prioritize their work in the region, it’s important for them to share their ideas and engage in international peace initiatives. “We’ve been advocating for a ceasefire for months, but it must be linked to a clear political horizon and end game, learning from the mistakes of Oslo. We propose a solution beyond traditional binaries, like one-state and two-state, transcending pro-Israel and pro-Palestine divides. We’re breaking away from the zero-sum game mentality. Connecting the ceasefire to a political horizon is crucial; otherwise, it becomes just another temporary measure that conceals the Occupation and obfuscates the reality of the conflict.”

In March, they accepted an invitation to speak in the European Parliament in Brussels. It seems most politicians have grown accustomed to years of Occupation and cycles of violence. But now, as the situation continues to escalate, the EU is grappling with what to do.

“We sat in meetings where we were asked: ‘What can we do?’” May recounts. “During the talks I started to feel angry, realizing the EU’s impotence. I thought, you have 100 tools, use them. That’s why you were created. I couldn’t bear hearing excuses, like the budget will come next year. It was embarrassing, at times even unbearable.”

One evening, Rula and May spoke in the spacious Brussel’s home of Simone Susskind, retired SP Belgium politician and peace activist. The room was quiet when May opened with these words: “I am not here to save Rula, I am here to secure a future for my kids. I know that the only way we can be safe is if Palestinians are safe.” It was the third time I had heard them speak, and I started recognizing their tropes. “The horror of October 7 made it clear to us that separation is not working.” This is a key point the initiative offers, to improve on the Oslo Accord’s principle of ethnic territorial separation. “In the seemingly most secure place we had, with the fanciest 10-meter-deep fence and the best technology, security was not achieved. We cannot put Palestinians behind a wall and forget about them. If anything, it has led us to this dramatic moment of loss and pain. What we offer is a paradigm shift.”

Sasha, a young Belgian man, identifies himself as the current leader of a progressive Jewish group: “I want to amplify voices and facilitate dialogue. But it’s hard. Most of our local Jewish community is moving away from progressives because of the rise of violence and antisemitic events.” While the small crowd in this Brussels living room is open to the ideas, the unspoken question lingers: “Yes, sure, but how?”

Shaqued Morag, the former head of Shalom Achshav (Peace Now), tells how she recently moved to Europe for a new position representing Israeli human rights organizations: “Peace Now’s target is to change opinions and foster a shift in Israeli society. Support for a peace agreement was almost mainstream during the Oslo Accords, but since October 7, public discussion [of peace] is barely possible. We must show the complexity of the situation and urge people not to choose sides, but to choose humanity. It’s incredibly difficult to be Jewish and left leaning; there’s a profound sense of isolation.

I recall the film “The Salesman” by the Maysles brothers. It tracks four salesmen as they journey through Florida, attempting to sell pricey Bible’s door-to-door in poorer areas. To me, May and Rula embody these salesmen; they are trying to sell something nobody wants to buy right now.

Rula speaks next. After a long day, fatigue has set in. She takes in a deep breath, followed by a prolonged silence, and then says: “I blame all of you. I’ll be blunt, I’ll be harsh. I don’t feel like doing the hope thing right now. I blame all of you. We’ve been telling you that we are heading towards a disaster. Especially you left Zionist liberals – by looking the other way, you let everything lead to this complete collapse of your society. But we Palestinians who live among you, we knew something like this would happen.” Rula looks at the crowd and the crowd at her. “Something is rotten in Israeli society, and you know it.”

Rula’s last words are hanging in the air, and May looks at her, burdened with the weight of responsibility. “Now I have to bring all the hope … and I don’t know if I have any right now,” she admits. “The most pragmatic thing to say is we don’t have a choice. There is no military solution.”

Like a rolling drum, they run from meeting to meeting the day after. The rumor about their visit spreads and everyone wants to meet them. People are clearing out their schedules to make place for them. 30 minutes meetings last more than an hour. There are also those who refuse to meet them publicly, wanting a confidential meeting to avoid public scrutiny. Things are sensitive due to the ongoing war, but curiosity is high.

In the end, their round of talks in the EU is considered a great success. Their approach, fueled by innovative solutions, has infused hope into the conversations. Their willingness to collaborate with stakeholders in search of meaningful solutions is deemed commendable. But more than anything, the fact that their proposals, informed by extensive research and expertise, originate from both Israeli and Palestinian experts is invaluable, especially for European experts and politicians.

During Rula and May’s last evening in Brussels a meeting is organized at Adva’s house; Adva is part of a local community of Ex-Israeli artists. They have been meeting since October 7, to talk and deal with the traumatic events and their identity as Israelis in Europe. On the phone when I told her I would be joining, Adva tells me that some of the members of their community are anti-Zionists. She hopes some Palestinians will join as well. I realize that I know some of the people who are coming. Later Rula and May also recognize some of the participants. May takes her shoes off and sits with her legs crossed on the couch. Rula, in a beautiful blue silk shirt, keeps her high heels on.

Having seen both these women engaging with various crowds, I’m understanding how the same message can take on different forms depending on the audience. Each audience uses distinct language and approaches the topic from different perspectives. Engaging in dialogue requires great delicacy; they must choose words carefully and introduce ideas in a manner that acknowledges their potential volatility.

“It’s nice to be among friends,” Rula says. “Our vision is not perfect. We want to speak and see how to improve it. We come together to co-create rather than negotiate. Ok, May,” she sighs, “you start.”

Their relationship is intriguing, as they keep drifting in and out of each other’s space. In the days together with them, I’m witnessing its evolution. Slowly, they begin to tango. They surf the waves of their own charisma, then dip into moments of hopelessness. They cope with fatigue and anger, yet somehow gather the strength to face each new day with renewed energy. However, as time passes, I cannot help but wonder: Will they endure?

“Classic white liberal Zionism has failed us — it has failed me,” May confesses, her tone carrying a personal weight. It is her father’s legacy that she is criticizing. “I had to unlearn some deeply ingrained principles. One significant shift was moving away from the notion of myself as an all-knowing human rights lawyer and embracing collaboration with the other side. That’s my transformation.”

“Most of you have read about our solutions, which may not be flawless, but the underlying principles hold promise. To share rather than divide.” May knows that most of the radical left people present in the room reject the Zionist state totally and believe that the path to decolonization lays in creating one civic reality — one democratic state for all. “Both Rula and I identify as post-nationalists, we are aware and supportive of all initiatives which promote equality and peace. However, let’s acknowledge that a one state solution is not realistic now, maybe later in the future. Right now, most Israelis and Palestinians do need a national self-determination. We seek to honor that reality and seize the opportunity it presents.” This statement raises a roar of disagreement in the small crowd that suspects it is just an update of 2 state solution that that perpetrates historical injustices.

Rula jumps in: “I fear that we may already be too late for any solution. Particularly with the current Israeli government and the radical factions of the religious nationalists already implementing their agendas of war and annexation. Our efforts are fueled by a sense of urgency. It’s not about seeking absolute justice, and there isn’t a singular path forward. There isn’t just one narrative defining my national identity. However, we are determined not to repeat the mistake of lacking an alternative solution to this violence.” The house cat comes to Rula and settles in her lap. May watches the scene unfold and complains: “These cats always prefer you!”

The promise of a familiar crowd doesn’t deliver an easier conversation; the opposite is true. This is a knowledgeable group, and their critiques quickly follow: Why acknowledge the nationalist aspirations of both Israelis and Palestinians? Why not just have one state? And what about this war? Where in the plan will we find reparations for the Palestinians? And how come you haven’t mentioned the word ‘genocide’?

A man who was sitting upright in the center of the room raises his hand. He introduces himself as a Palestinian from Gaza. He doesn’t care if his government will be Jewish or Muslim, he says, as long as it’s not corrupt, so long as he and his kids are free and equal. “As a Gazan I do not wish to divide [the country]; I want just one civic reality. There’s a gap between the Palestinian diaspora and those of us who live on the ground. We need to get out of the illusion. We just want to live.” My eyes fill with tears.

As the evening draws to an end and Rula tries to wrap it up, a man sitting on the side with a keffiyeh around his shoulders asks for permission to speak his truth: “I am Palestinian, and I am here with a different agenda. We are promoting another framework. Our plan is for a single Palestinian democratic state. I mean, Jewish people with an Israeli passport can stay if they wish, but we will abolish the Aliyah and totally abolish the Zionist state. And we will proceed toward creating a new democratic state.”

Rula, annoyed, immediately reacts: “Oh yeah, and how do you propose doing this?” “With armed resistance,” he answers, provocatively directing his gaze at her. “For real?” she replies. “Do you really see us gaining this kind of military power to defeat Israel?”

In the cab back to the hotel Rula confesses: “Since this war began, I lose my patience very quickly, especially with people who sit somewhere far away and say that there are no solutions and refuse to consider new ideas. So, what do you want, for us here to live forever in war? Armed resistance, really? I don’t want this to happen to my friends, to my colleagues. There are many Israelis I know, and they are people too. I can’t accept this.”

The electric cab falls silent when stopped at the red light. We observe the square, the walls decked with “Decolonize Palestine” posters and banners. “So, when we talk about decolonizing Palestine, the big question is: How? Nobody knows. Sure, we can philosophize about it all day long. But in the end, there are people living their lives day in and day out, who have a national vision, who want self-definition. How can we, as academics, approach them with a paternalistic attitude, acting like we know it all? And believe me, I say this as an academic myself. We tend to think we have all the answers because we can dissect history, politics, and economics. We academics think we know it all, but that is simply not true.”

All over Europe, swelling protests wave Palestinian flags, bringing the Palestinian cause into the international spotlight. Rula welcomes this surge of interest and solidarity. “Solidarity is crucial, and it’s encouraging to see. But how does it turn into real support? Protests alone will not save us,” she says. Currently, many Palestinians harbor hopes of overthrowing Israel through force, with support from the Arab world. But the 2020 Abraham Accords have underscored the Arab world’s willingness to progress without addressing the Palestinian issue. Rula continues, “In the end, we want to live, in our own state, that’s what most Palestinians want.”

I observe May and Rula leaning against the cab windows in the quiet, empty streets of Brussels. Tomorrow, I return to Amsterdam, and they will land at Ben Gurion Airport. Since the war, the airport is deserted, decorated with “Together we will win” banners and with posters featuring the faces of the hostages who are still in captivity in Gaza. I can picture them sharing a cab to Jerusalem, dropping off May at her home, then Rula continuing toward her home in Ramallah, navigating militarized checkpoints to get there. We travel through time, through our past into the future these two women are working so hard to imagine. Meanwhile, the present pulls at our jackets; the absence of a ceasefire is maddening. It is inhumane and cruel for the people of Gaza, for the hostages, and for everyone else between the river and the sea. This must be the last war.

- Text By

- Nirit Peled

- Published on

- De Groene Amsterdammer

- Chief Editor

- Xandra Schutten

- Photos By

- Nirit Peled

- Translation (EN–NL)

- Menno Grootveld

- Edited by (EN)

- Rachel Tzvia Back